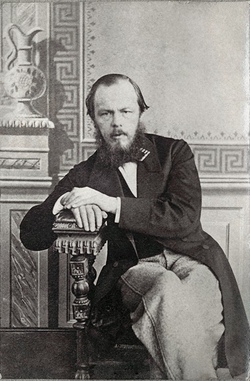

You might not have expected to see Dostoevsky’s name on a site all about online roulette, but believe it or not, the famous Russian writer had a bit of a gambling problem.

You might not have expected to see Dostoevsky’s name on a site all about online roulette, but believe it or not, the famous Russian writer had a bit of a gambling problem.

When we say ‘a bit of a gambling problem’, we really mean a serious roulette addiction.

He is a rarity on this list of famous players because rather than being famous in roulette playing circles for having some sort of impact on the game, he is a roulette player who happens to be best known for something else.

The man most famous for writing Crime and Punishment had an incredibly dramatic life even before he discovered roulette, but after first losing on the roulette wheel he spent almost a decade weighed down by addiction, constantly back and forth to the casino and unable to control himself.

Where it all started though, was back in Russia where he was born in 1821, so he was around at the same time as Francois and Louis Blanc. Indeed, the pair would indirectly have a huge influence on his life as you will read later on.

Sentenced to Death

Fyodor Dostoevsky’s bad luck started early, losing his mother aged just 16 and sadly losing his father two years later, making him an orphan at 18. He wasn’t completely alone though, he had a brother.

Despite graduating from engineering college, his real passion was for writing, and his first book, Poor Folk, brought him much success at just 25 years old. A bad case of second novel syndrome brought him nothing but bad reviews though, and things were about to get much worse.

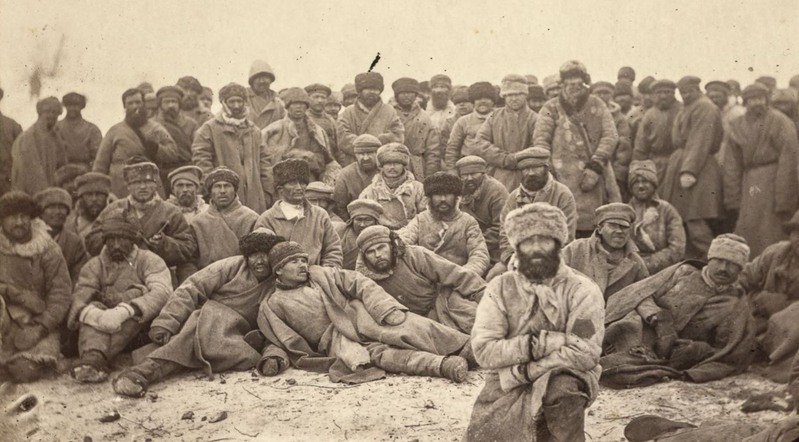

Fyodor was arrested and sentenced to death after engaging in anti-government meetings and campaigning for the freedom of serfs – servants or slaves in Russia at the time.

He was even led out in front of the firing squad, but in a moment worthy of a Hollywood movie climax, just as he was about to be tied to the post his sentence was changed to 4 years hard labour in Siberia, working alongside hardened criminals.

After his time in Siberia he spent 5 years working for the army before finally being given his freedom aged 38, and he began writing again as well as starting a magazine with his brother which did well.

It is around this time, in his early 40’s, when Dostoevsky first discovers roulette during a trip to Europe, where the afore mentioned Blanc brothers had recently revolutionised the game by reducing the house edge.

He lost everything he had, and was forced to write begging letters in order to get back home to Russia, and pawn off his possessions to survive the journey.

Excerpts from his letters clearly show the early signs of a gambling problem:

This was the beginning of a downward spiral that would take hold a few years later.

The Roulette Wheel Hypnotizes Dostoevsky

Barely back in his home country for a year, and Fyodor is dealt two crushing blows.

His dearly beloved wife, Maria, succumbed to tuberculosis in 1864, and just two months later his brother, Mikhail, also passed away from a combination of stress and liver problems.

This left Fyodor bereft, with mounting debt thanks to the new magazine he and his brother had launched, and in his desperation he signed a very dangerous contract with a publisher named Stellovsky.

The deal was that Dostoevsky would deliver a new novel within the year, or else Stellovsky would own the rights to all of his work past and future for the next nine years. The downside was huge, and Dostoevsky decided to run away to Europe for a break to get away from his problems.

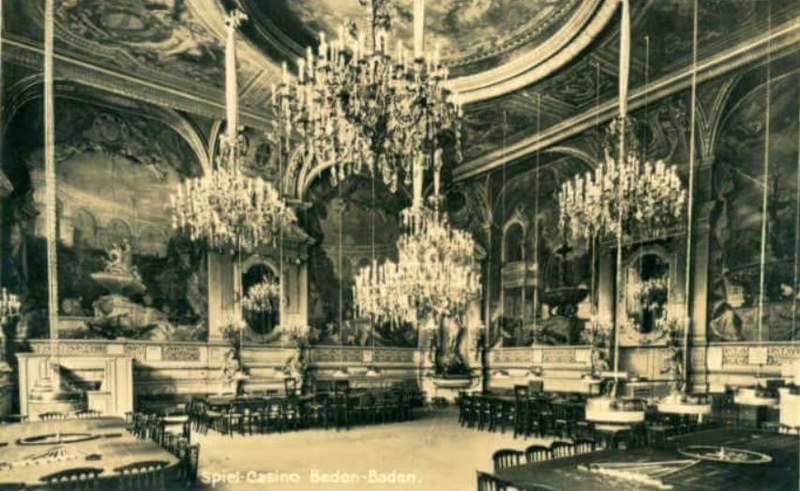

Back on the continent where he first discovered roulette, he revisited the casino and attempted to win enough money to solve all of his financial problems, but of course, he lost the lot, only worsening his situation.

Once again, he had to write begging letters to friends asking for money:

Back in Russia his time was running out to fulfil the terms of his contract, and so he hired a secretary to write shorthand as he dictated and so speed up the process. The end result was The Gambler, a book heavily inspired by his own experiences of gambling, and it was completed in just 26 days.

Dostoevsky did more than just honour his contract to Stellovsky that month though, he also met his second wife, Anna – she was the secretary he hired to help him complete the novel, and she would be a loyal wife to him for the rest of his life, and hers.

The Never Ending Honeymoon

The pair married in 1867, and their 3 month honeymoon ended up lasting 4 years, partly because Fyodor used Europe and the roulette table as a way to escape his creditors.

The couple spent much time in places like Baden Baden, Bad Homburg, and Wiesbaden, all famous gambling hotspots of the day, again thanks to the Blanc brother’s involvement.

Dostoevsky continually attempted to win enough money to get himself out of debt, regularly encouraged by big wins that he then squandered by being unable to walk away while he was on top. He even seemed to understand his condition, despite not being able to control it.

This is from an 1867 letter to a friend:

This pattern was repeated for the next few years, with his poor but devoted wife following him around Europe and being abandoned for the casino towns time and time again.

They even lost a baby in 1868, a further hammer blow to Dostoevsky’s nerves, who is said to have “wept and sobbed like a woman is despair”.

They had a second child in late 1869, Lyubochka, and 18 months later Dostoevsky had a startling vision that would change his life for the better forever.

In a dream, he saw his father who prophesised a ‘dreadful disaster’, that seemed to involved Anna getting sick. This seriously affected Fyodor, having already lost one wife, a daughter, and all of his own family, and he vowed to never gamble again.

In a letter from 1871 shortly after the dream, he wrote to Anna:

He stuck to his promise.

He stuck to his promise.

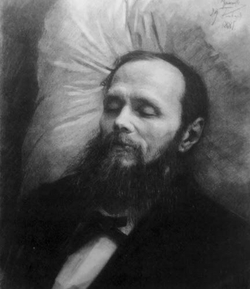

From that point until his death in 1880, aged just 59, Dostoevsky never gambled again.

He and Anna would have two further children, although tragically one of them, a son, inherited epilepsy from his father and died of a fit aged 3. Their bond would never be broken though, and even after his death, Anna never remarried, and later commented on Dostoevsky’s devotion to her, remarking that she never understood what Fyodor saw in her.

Dostoevsky was a brilliant man in many ways, a literary genius in the view of many; yet some of his best works were inspired by the darkest times in his life, and gambling addiction played a big part in that.

It just goes to show that problem gambling has always existed, and it can get hold of anyone, rich or poor, educated or uneducated.

The Gambler

Since this book was based on Dostoevsky’s own experiences of gambling, and indeed was written to get him out of a gamble of sorts of his own, it’s interesting to look at what it was is about and how roulette is described.

Since this book was based on Dostoevsky’s own experiences of gambling, and indeed was written to get him out of a gamble of sorts of his own, it’s interesting to look at what it was is about and how roulette is described.

The plot follows a tutor hired by a previously wealthy Russian family who are now riddled with debt. The family are living in a hotel in Germany and hear that the wealthy grandmother back in Moscow is ill. Expecting her death and a swift inheritance, the family think their money problems are over.

At the same time, the tutor falls in love with the niece of the family, who uses him to place bets for her on the roulette to try and solve some of the family’s financial problems. He wins but the niece is cruel to him, making him behave rudely towards the local nobility and losing him his job.

Next, the grandmother turns up alive and well in Germany, and fully aware that the family was hoping she would die. She swears they will not get her money and asks the tutor to show her around town because she wants to gamble, putting the family’s future at risk.

The rest of the story is full of big wins and big losses, lying and cheating lovers, and the tutor left gambling to survive despite having become a rich man at the roulette table.

Apart from being a good story though, it’s a fascinating insight into the mind of a compulsive gambler.

Descriptions of Gambling

What is really compelling, is some of Dostoevsky’s descriptions of entering a casino for the first time:

“In the first place it all struck me as so dirty, somehow, morally horrid and dirty. I am not speaking at all of the greedy, uneasy faces which by dozens, even hundreds, crowd round the gambling tables. I see absolutely nothing dirty in the wish to win as quickly and as much as possible.”

“What was particularly ugly at first sight, in all the rabble round the roulette table, was the respect they paid to that pursuit, the solemnity and even reverence with which they all crowded around the tables.”

And this passage describing the feeling a compulsive gambler experiences while winning could have come from Dostoevsky’s own mouth:

“At that point I ought to have gone away, but a strange sensation rose up in me, a sort of defiance of fate, a desire to challenge it, to put out my tongue at it.”

The book shows that Fyodor had a very good grasp of what was happening to him, but what he did not have was the willpower to control it.

“Sometimes the wildest idea, the most apparently impossible thought, takes possession of one’s mind so strongly that one accepts it at last as something substantial.”

Instead, he created a world with different rules where he could beat the game and become rich, perhaps because, as a writer, he was used to creating stories in which he could control the outcome.

But roulette isn’t a story, it’s a real game with fixed odds, and no amount of imagination or creative thinking can change that, as Dostoevsky found out many times over.