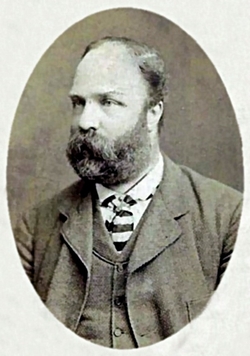

Joseph Hobson Jagger was born in 1830 in a village called Shelf, Yorkshire, and spent his working life as an engineer in the mills that dominated the Northern working towns of the Victorian era.

Joseph Hobson Jagger was born in 1830 in a village called Shelf, Yorkshire, and spent his working life as an engineer in the mills that dominated the Northern working towns of the Victorian era.

He is perhaps the most unlikely person of all of those who have broken the bank at Monte Carlo, but in the early 1880’s that is exactly what he did.

After working his way up in industry and teaching himself to read and write, Jagger had set up his own textile business in an attempt to capitalise on the cotton boom in Manchester. However, the recession hit soon after and his business failed in 1861 – he lost everything, leaving him almost bankrupt, on the verge of going to debtors prison, and with a large family to support.

So Jagger came up with a – sightly desperate it has to be said – plan. As an engineer, Jagger doubted that the roulette wheel could be truly unbiased, and so he developed an idea that would solve his money worries forever.

He would travel to Monte Carlo, observe the roulette wheels and identify any bias, and then exploit that bias using money he had borrowed from friends and family.

Remember, this was around 1880, there were no planes, this sort of journey was expensive and took a long time. Jagger would be gone for months, so this was an extremely bold move.

Spotting Wheel Bias in Monte Carlo

Credit: Matthew Hartley Flickr

Jagger had enlisted the help of his eldest son, Alfred, as well as his nephew, Oates, and together they spent a month observing the wheels in the famous casino and recording the results. Some say he enlisted further help once in Monaco, but the facts here are unclear.

What is certain though, is that by the end of his intelligence gathering mission, Jagger had identified one out of the six wheels with a definite bias towards a certain set of numbers.

These were:

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 17

- 22

- 28

- 29

Now confident in his bias spotting abilities, Jagger was ready to put his money to work, and began gambling on roulette.

He was careful not to arouse suspicion unnecessarily, but he was so successful that eventually he was impossible to ignore. Other gamblers were even starting to copy his bets in an attempt to piggy back on his success.

The Casino Fights Back

After days of haemorrhaging money the casino was onto Jagger. They may not have been able to understand how he was doing it, but they knew he was exploiting the game in some way.

After days of haemorrhaging money the casino was onto Jagger. They may not have been able to understand how he was doing it, but they knew he was exploiting the game in some way.

After a few underhand distraction tactics failed, such as sending over flirting women to interrupt him or clumsy staff who would spill drinks, they had to come up with something else.

They decided to switch the wheel at the table Jagger had been playing overnight, so that when he came back in the morning he would unknowingly be playing on a different wheel.

It worked, and Jagger began to lose money. However, this aroused his suspicions and he soon noticed that the wheel was in fact different. The wheel he had been playing on had a small scratch he had taken note of, and that scratch was no longer there.

It didn’t take him long to find the biased wheel in its new location, and Jagger was soon back to his winning ways.

The casino’s next step was to change the dividers/frets between wheels (the little slats that separate the numbers and allow the ball to settle). This had a direct affect on the wheel bias and so Joseph’s plan was scuppered, but he didn’t know that yet.

After two days of negative results he had worked out that something must be wrong, but since he couldn’t work out exactly what had changed or how to combat it, he cut his losses and returned to England a rich man nevertheless.

He had outsmarted the casino to the tune of £65,000, worth around £7.5 million today, and he knew when to quit.

Back to Bradford

Joseph Jagger spent a decade living as a wealthy man, investing much of his fortune in property for himself and his extended family in and around Bradford, before sadly dying aged 61 in 1890.

Joseph Jagger spent a decade living as a wealthy man, investing much of his fortune in property for himself and his extended family in and around Bradford, before sadly dying aged 61 in 1890.

The family didn’t stay wealthy for long. Jagger gave much of his fortune away and never lived a life of luxury, in fact, he went completely under the radar once back home, and his story was all but lost too. By the time he died his will was not that of a millionaire.

What was left was distributed among his four children, who no doubt led comfortable lives, but the money did not last for generations. His story was passed down through the family though, fascinating his great-great-great niece so much that she went to great lengths to uncover the truth of it.

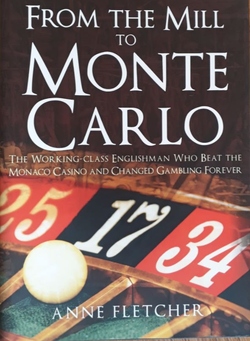

Anne Fletcher, a historian as luck would have it, thoroughly researched the story of her ancestor and wrote ‘From the Mill to Monte Carlo’ in 2018, chronicling Jagger’s story from beginning to end, and even exploring the lives of his descendants.

There have also been a few myths about Joseph Jagger.

The first is that Mick Jagger, of The Rolling Stones fame, is a distant relative. While not inconceivable (Mick’s grandfather was from Yorkshire), there is no direct evidence of the connection.

It has also been reported that the song, “The Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo” is about Joseph Jagger, but this is also untrue. It is actually about Charles Wells, a gambler and fraudster.